When driving along one of the many highways in British Columbia, you may have come across a sign that says “Report All Poachers and Polluters” or RAPP.

The sign lists a phone number citizens can call to report people who are illegally hunting or dumping garbage. The reports go to the Conservation Officer Service (COS) for action from conservation officers like Mike Sanderson, a sergeant in the Thompson-Nicola zone. But what exactly do conservation officers do, and how did the position become what it is today?

The precursor to COS was formed in May 1905. Originally called the office of the Provincial Game and Forest Warden, the offices mandate was to protect game, or animals hunted for sport.

From a fairly laidback origin story, where the first wardens could be given a badge and were “never heard from again,” today conservation officers are responsible for enforcing 20 laws across federal and provincial governments.

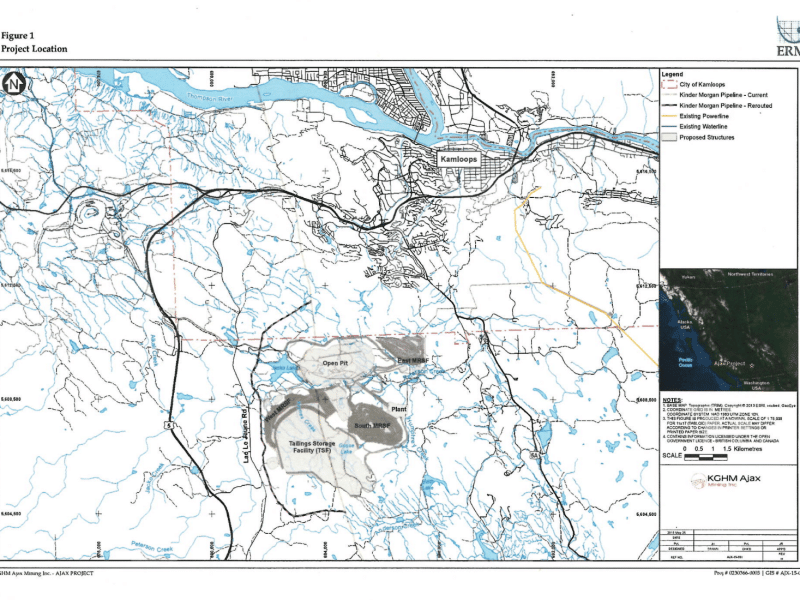

There are two district offices Sanderson’s detachment covers – one in Kamloops and a second in Merritt. Merritt’s district goes down towards Princeton and Manning Park. Around Logan Lake, the district shifts to the Kamloops detachment, ranging from Ashcroft and Cache Creek to Barriere and the Shuswap.

While much of a conservation officer’s duties relate to human-animal conflicts, be it bears, cougars, wolves, coyotes or even aggressive deer, Sanderson explained the job goes well beyond these issues.

“People think we’re here to deal with the bears, but there’s quite a diverse and broad mandate within our job,” Sanderson said.

Among his many duties, Sanderson is responsible for enforcing hunting and fishing laws, the Off-Road Vehicle Act and the Environmental Management Act. He also works closely with the environmental protection division of the provincial government to investigate permit violations.

COS was even called into the northern Shuswap this wildfire season for evacuation and security, as well as the Embleton wildfire in 2021.

There are many responsibilities involved for a large geography, with five officers between the two zones. The staff per area covered is a topic that comes up in conversations, Sanderson said.

“A lot of people, they’re kind of surprised by the area to cover in the mandate that we have in terms of enforcement and even just public safety with respect to human-wildlife conflict,” Sanderson said. “It seems like we’re short, for sure.”

This results in a reactive versus proactive approach to patrolling a province popular for recreational activities.

“It’s frustrating when you can’t get to all the calls that are out there.”

Alongside the day-to-day activities of his job, there’s also training on equipment and case law, as COS is a branch of law enforcement. There are firearms qualifications and defence training to maintain, as well as staying up-to-date on predator knowledge, keeping current on changing case law and working with Indigenous communities.

“[Indigenous communities] often work with their eyes and ears on the land base, through different Guardian programs or just in general on their own,” Sanderson said.

Guardian programs help fill the gap in patrolling vast expanses of land while ensuring Indigenous stewards, who intimately know the land, maintain their sovereignty.

However, even if conservation officers can’t get to every call, contacting the office is important to prevent worst-case outcomes for animals. So, too, is keeping in contact with local associations, like Sun Peaks Bear Aware, according to Sanderson.

“By not calling in a sighting or all the way through to a conflict, the conservation officers don’t have any opportunities to intervene early,” retired large carnivore specialist Tony Hamilton told SPIN during an interview for a story on Black bears in Sun Peaks.

This fall, the COS responded to a bear who was habituated to humans in the village, and the officers had to “destroy” – or kill the bear. But by alerting conservation officers to human-bear interaction on first sight, animal behaviour can be altered.

“The worst part of our job is having to kill healthy wildlife,” Sanderson said of the bear who accessed garbage in Sun Peaks and was subsequently killed. “It’s not their fault – they’re doing what they are biologically programmed to do – find the easiest food source and put weight on to den for the winter.”

For example, this year’s berry crop was lower than usual, according to Olivier Jumeau, whose research focuses on Black bear scat in Sun Peaks. He only found two samples this summer with berry consumption, possibly increasing the number of human-bear interactions as the animals seek nutrition elsewhere.

“People can’t be naive in assessing how rapidly a bear can get into garbage,” Sun Peaks Bear Aware representative, Karen Lara said. “It will frequently return to that spot because once it’s accessible, it’s highlighted in their brains as an optimal food source.”

There are a handful of ways to reduce animal interaction with humans, limiting the amount of calls conservation officers need to respond to in their large regions. Namely, securing garbage properly, especially during mating and pre-hibernation seasons from April to November, when bears are looking to bulk up.

When all steps are taken to prevent animal habituation, conservation officers s can focus more energy on the aspects of the job that allow them to thrive alongside wildlife.

“Most of us get in this job because we love that environment,” Sanderson said. “We love wildlife, and we want to make sure that it’s protected for everyone’s benefit for future generations as well.”

What did you think of this story?

Sun Peaks Independent News is your essential source for community news in Sun Peaks. Your feedback after we publish a story helps ensure we're always improving our reporting to better serve you.