In the months following the ruling in Cowichan Tribes v. Canada recognizing Aboriginal title rights to parts of Richmond and the Fraser River, many across British Columbia and particularly those in Kamloops (Tk’emlúps) and Sun Peaks have wondered: What are the implications of land claims on personal property rights?

Tk̓emlúps te Secwépemc and the City of Kamloops shared a statement Dec. 12, 2025 providing clarity on the Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwepemc Nation’s Aboriginal title claim to a 1.25 million hectare portion of Secwepemc territory.

The joint statement shared that, despite being filed in 2015, the land claim remains in early stages, adding, “the fundamentals of property ownership in Kamloops remain unchanged and day-to-day life continues as normal.”

No declarations have been made and it clarified that “the claim does not seek private or city-owned land.”

Both governments called for patience from the public and have encouraged residents to seek factual information.

Sun Peaks Independent News reached out to the City of Kamloops and Tk̓emlúps te Secwépemc for further comment but both declined. With many readers submitting questions regarding land claims, and lots of discourse and misconceptions around the implications of court outcomes, Sun Peaks Independent News spoke with experts to learn more.

What are land claims and why do land claim court cases exist?

Chrystie Stewart is a lawyer at Alexander and Stewart Lawyers. She is also a band member of Tkʼemlúps te Secwépemc. Although she is a member, she does not speak on their behalf or represent them in any way. She has ample understanding on the topic thanks to her work on many Indigenous issues.

The lawsuit most folks are aware of or discussing right now, The Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwepemc Nation Aboriginal Title claim, is not new Stewart said.

“It’s many years old, and it’s come to light because of the Cowichan decision,” Stewart said.

While Indigenous peoples have had relationships to the land for millenia, Aboriginal title has its roots in 1763, when the British Crown issued the Royal Proclamation recognizing Aboriginal title during European settlement.

A series of numbered treaties were signed in Eastern Canada to “extinguish” these Indigenous rights in exchange for treaty rights like long-term access to health care, education, their lands and to benefit from them.

“At least in much of B.C., no treaties were signed, and this was a deliberate colonial policy,” Mae Price explained, a lawyer for JFK law and co-author of an article that explained the Cowichan Tribes decision.

This means the land was never lawfully ceded, which is why the City of Kamloops states it is “located on Tk’emlúps te Secwe̓pemc territory within the unceded ancestral lands of the Secwépemc Nation.”

In Interior B.C., like many other regions, early settler colonial governments sold land they didn’t own to private interests, most often without treaties in place, leaving First Nations to turn to the courts for recognition of land ownership.

“It’s just been the assumption or the position of colonial governments and settler society that it is their land,” Price said. “We know that is not true. We want to develop healthy and respectful relationships with Indigenous communities. To do that we need to reconcile with the fact that their land was taken from them. ”

While the courts can provide an answer as to who has the right to the land “based on the tests that they have developed for determining whether or not Aboriginal title exists,” Price said the courtroom is not the best place to deal with this.

This is why, in many cases the courts urge Canadian and Indigenous governments to negotiate these issues outside of the courtroom, Price explained.

In cases where the land claim is on Crown land, this may involve land being returned to a First Nation. The resolution could also involve shared decision-making or revenue sharing.

“At the end of the day, negotiations don’t always work,” she added. “There’s been a lot of issues with negotiating land claims in B.C. The process is really dragged on for a lot of communities, so sometimes you do need to resort to the courts.”

Understanding the Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwepemc Nation’s Aboriginal Title Claim

The Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwepemc Nation, a governance division representing Tk̓emlúps te Secwépemc and Skeetchestn Indian Band, put forward an Aboriginal title claim in 2015 to the B.C. Supreme Court asserted Aboriginal title and rights to the whole of the Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwepemc territory.

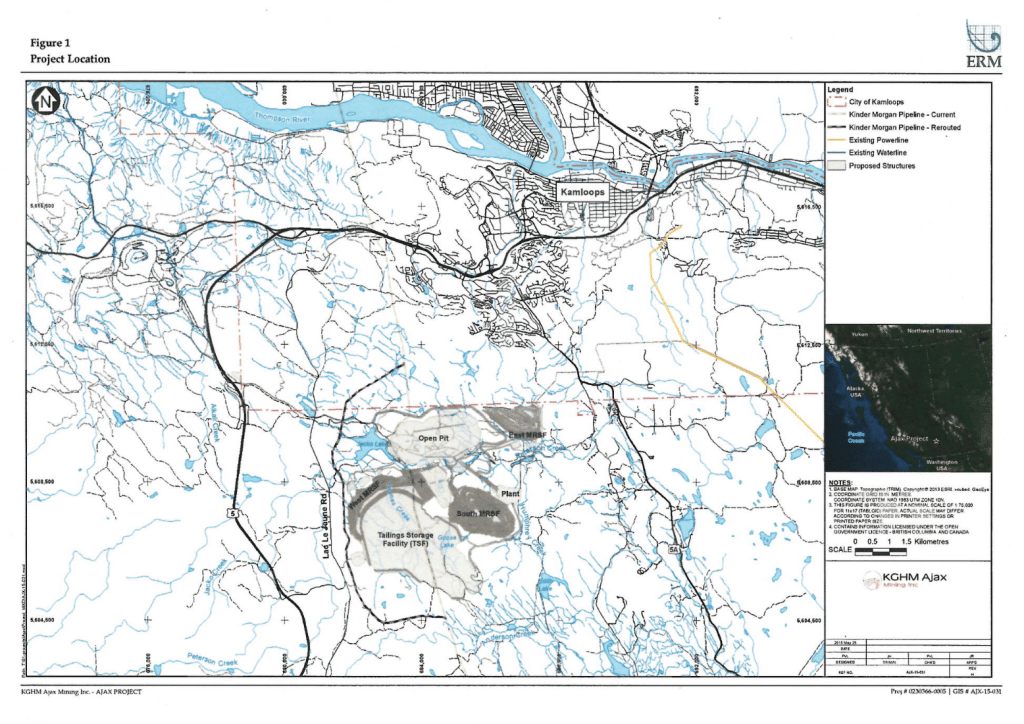

“The Secwepemc Nation seeks declarations of Aboriginal rights and title in relation to part of its traditional territory, damages in respect of unjust infringements of those Aboriginal rights and title, and interim and permanent injunctions preventing activities in relation to a project known as the Ajax Mine,” the document stated.

The activities it refers to is the KGHM Ajax Copper-Gold project, a proposed open-pit expansion to a former copper and gold mine with a production capacity of up to 24 million tonnes of ore per year.

Implicated in this activity is the Jacko Lake area, a sacred land known as Pípsell to the Secwépemc officially designated as a Secwépemc Nation Cultural Heritage Site in 2017.

That year, the nation also conducted its own impact assessment of the proposed Ajax mining project and British Columbia declined the issuance of an Environmental Assessment Certificate for the mine.

However in 2022, Abacus Mining and Exploration Inc. announced it will revisit the planning process to reactivate the project. In 2025, the company provided an update on the progress made towards the project, stating since 2017, “KGHM in consultation with Abacus has worked to re-evaluate the project, taking into account relations with all project stakeholders, especially First Nations.”

Misconceptions about land claims

The biggest misconception at the moment is the impact land claims have on private property.

Property rights are some of the most strongly protected rights in Canadian law Stewart said, adding they are stated in the constitution. But in the Cowichan decision, the court issued Aboriginal title over certain private property.

“That’s the first time that has happened,” Price said. “There’s only ever been three successful Aboriginal title claims, and this was the first time that declarations have been issued in respect of private property. So that has caused a lot of confusion, and I think a lot of fear for people.”

“It only resulted in a declaration of Aboriginal title, and declaration is a sort of statement on the current state of affairs,” Price continues.

Furthermore, it applied only to those lands, no other property elsewhere in B.C.

“I think that’s where people need to understand that there is not a chance that the band is going to suddenly just assume control over all of the properties,” Stewart said.

Stewart also broke down some misconceptions, explaining there is jurisdictional conflict between the federal lands and provincial lands.

“The claims that are being made are not for the federal lands. That land has already been reserved for the use and benefit of Indigenous people. The claim was for the provincial lands,” she explained.

Stewart has noticed confusion and surprise that these cases aren’t settled in B.C., but Price added that much of B.C. is covered by “the asserted traditional territory of Indigenous communities,” Price said.

Another misconception is that going to court for a land claim is an easy process.

“Most of the Aboriginal title claims that have proceeded have been very lengthy processes,” Price said. “The Cowichan case lasted upwards of 500 trial days spanning over five years. And to get from the point of filing the claim to a decision was over of 10 years.”

Other experts have noted the very high bar of evidence the judge saw in this case, which would be very difficult for other nations to replicate.

This is not counting the money communities need to have to build a successful case.

“Everyone needs to be pushing the B.C. government to negotiate solutions with Indigenous communities, because litigation is not the best place for it to be dealt with,” Price said. “[The province] is not addressing it in a timely and meaningful way. I think that this Cowichan decision has prompted them to rethink their approach, and have hopefully pushed them to engage in those negotiations in a more meaningful way.”

In the case of land claims B.C. has not done much to address outstanding claims.

“A lot of this misrepresentation is that if first nations have title to the land, that they’re going to take the land. I think that’s the kind of the worst part about all of this language that’s being tossed around,” Stewart said. “I think that there’s more uncertainty if there’s land claims that aren’t settled.”

What did you think of this story?

Sun Peaks Independent News is your essential source for community news in Sun Peaks. Your feedback after we publish a story helps ensure we're always improving our reporting to better serve you.